What Are You Passing Down?

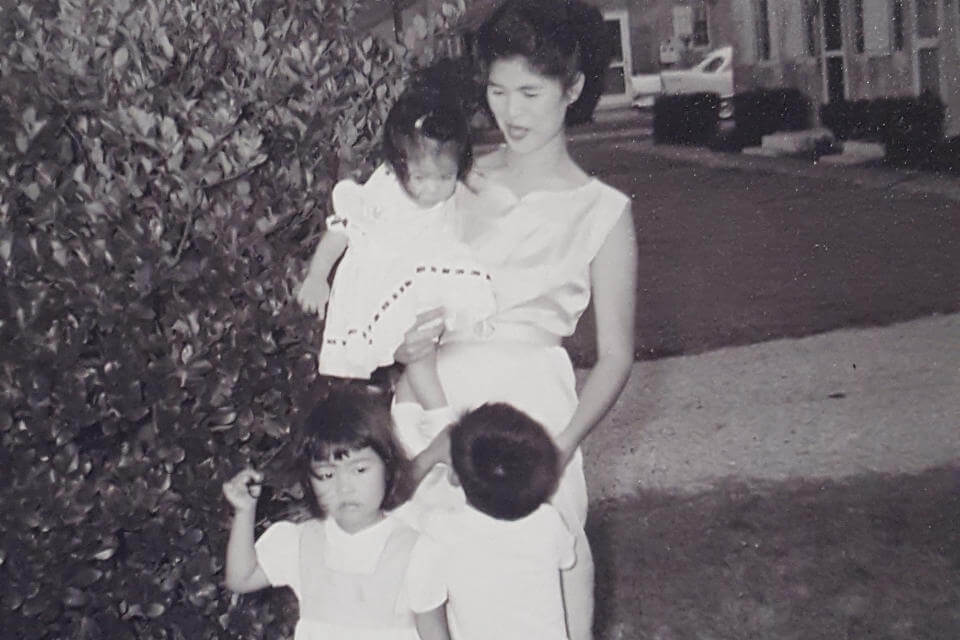

It’s the mid-‘60s in South Carolina. As soon as their father parks the car at the roadside diner just inside the South Carolina border, Cindy and her little brother and sister pile out, more than ready for a break from the long drive from Virginia. They chase each other to the water fountains and then skid to a halt.

Two water fountains are divided by a chain. They stare at them. Coming from living on the Navy base in Norfolk, they’ve never seen anything like this.

Over one fountain is written: Colored. Over the other: White.

Reading them, Cindy’s brother, Eddie, brightens and shoves the barrier away, running to be first in the colored line. “I want blue!” he shouts. “I want to be blue!”

When the water stays clear and his skin stays the same color, he turns to their parents, so disappointed. “Why say that when it’s not any different?”

Two water fountains are divided by a chain. They stare at them. Coming from living on the Navy base in Norfolk, they’ve never seen anything like this.

Over one fountain is written: Colored. Over the other: White.

Reading them, Cindy’s brother, Eddie, brightens and shoves the barrier away, running to be first in the colored line. “I want blue!” he shouts. “I want to be blue!”

When the water stays clear and his skin stays the same color, he turns to their parents, so disappointed. “Why say that when it’s not any different?”

This is Cindy’s earliest memory of racism—during segregation—seen through the innocent eyes of children.

A military brat and first generation Filipino American, Cindy was used to living around people who looked different from her. People in the military were from all over. It was normal to ride her bike down the sidewalk on the Navy base in Norfolk, past each tiny yard, waving at her friends’ and their parents who often had different skin colors.

But they weren’t in Norfolk anymore.

A military brat and first generation Filipino American, Cindy was used to living around people who looked different from her. People in the military were from all over. It was normal to ride her bike down the sidewalk on the Navy base in Norfolk, past each tiny yard, waving at her friends’ and their parents who often had different skin colors.

But they weren’t in Norfolk anymore.

Not in Norfolk Anymore

The same day, traveling down from Virginia, as they neared Charleston where her father would be stationed, Cindy would witness a man refuse her father and her Uncle Mike entrance to the restroom. A deep sense of unease took root. Something was very wrong.

Arriving at the Navy base in Charleston, Cindy was relieved to find much of what she was used to—but with one important difference. Unlike Norfolk, the elementary school was off-base in the local town.

First day of third grade, the kids stared at her. “What are you?” they asked.

The question came from kids who were White, and kids who were Black. But she wasn’t either one. “I’m brown,” she said, feeling separate and alone like she never had before.

“How'd you get here?”

“I was born here.”

“Do you speak English?”

“Obviously.”

Arriving at the Navy base in Charleston, Cindy was relieved to find much of what she was used to—but with one important difference. Unlike Norfolk, the elementary school was off-base in the local town.

First day of third grade, the kids stared at her. “What are you?” they asked.

The question came from kids who were White, and kids who were Black. But she wasn’t either one. “I’m brown,” she said, feeling separate and alone like she never had before.

“How'd you get here?”

“I was born here.”

“Do you speak English?”

“Obviously.”

“It’s a terrible feeling to be embarrassed, to be ashamed for just having the skin color you do.”

This line of questioning made Cindy, a shy child by nature, more so. “Growing up,” Cindy said, “I’d get dirty looks from people I’d never met. It’s a terrible feeling to be embarrassed, to be ashamed for just having the skin color you do.” She never knew what to expect from people—and that included the family of the man she would eventually marry.

What are you?

Cindy met Benny, her future husband, on a blind date. “He was a White country boy,” Cindy said. “In those early days, he called me his ‘yellow girl.’ Now he wouldn’t think of calling me that. But at the time, my biggest worry was that his family wouldn’t like me. I knew they had some murky ties in their history. But they’ve always treated me fine. There’s just so much to the way you’re perceived that has little to do with who you really are,” she said. “I have a thick Southern accent since I’ve lived in the South most of my life now. It’s still funny how people I’ve only talked to on the phone are surprised when they meet me in person. With my accent, I don’t look like what they expect.”

“You want your kids to have a better life than you did—not have to deal with the same painful things.”

Throughout her life, Cindy has heard that same question: What are you? And she has seen it affect her children, too. “My daughter is pale like her dad, while my son inherited my father’s darker coloring. My son’s had a harder time with racism over the years. You want your kids to have a better life than you did—not have to deal with the same painful things. We all bleed red.”

Accepted

Even today, whenever entering a new place, Cindy is on guard, unsure whether she will be accepted. Walking through the doors of Seacoast’s North Charleston Campus for the first time, she was nervous. “But I felt welcomed and comfortable right away,” she said. “I saw such diversity in the people around me. When I started to sing, adding my voice to theirs, the hair on the back of my neck stood up. I felt nobody was better than anyone else. I knew I was home.”

What are you? Cindy’s answer now: "I am a woman who loves God, my family, and my church. I am a grandmother who loves and revels in how my grandchildren’s skin is a range of beautiful colors... I am me. A child of God. And I am hoping in a new beginning for all of us."

Follow us for up-to-date information